⏱️ 5 min read

When James Cameron's epic film "Titanic" hit theaters in 1997, it became a cultural phenomenon that captured hearts worldwide. While audiences marveled at the stunning visual effects and tragic love story, few realized that the director's obsession with authenticity led him to undertake one of the most ambitious documentary projects in cinema history. Cameron didn't just recreate the Titanic on soundstages—he personally descended nearly 12,500 feet below the ocean's surface to film the actual wreck site, making multiple dives that would inform every detail of his blockbuster production.

The Director's Deep-Sea Obsession

James Cameron's fascination with the Titanic began long before he pitched the film to Hollywood studios. As an accomplished deep-sea explorer and filmmaker, Cameron had harbored a lifelong interest in shipwrecks and underwater exploration. His passion for diving and marine technology wasn't merely a hobby—it was an integral part of his creative process. Cameron convinced 20th Century Fox and Paramount Pictures to fund not just a movie, but also a series of expeditions to the actual Titanic wreck site, arguing that authentic footage would elevate the film beyond typical Hollywood spectacle.

Between 1995 and 2001, Cameron completed 33 dives to the Titanic wreck, spending more time at the site than the ship's captain did during its maiden voyage. These weren't brief visits; each dive lasted between 15 to 17 hours, with Cameron squeezed inside a small submersible designed to withstand the crushing pressure of the deep Atlantic Ocean. The wreck sits approximately 370 miles off the coast of Newfoundland, presenting logistical challenges that would deter most filmmakers.

Pushing Technological Boundaries

Cameron's expeditions weren't undertaken with standard equipment. The director worked with Russian scientists and engineers to develop specialized camera systems that could function at extreme depths. He helped design remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) small enough to navigate through the Titanic's interior corridors, capturing footage that had never been seen before. These tiny robots, nicknamed "Jake" and "Elwood" after the Blues Brothers, could squeeze through openings as small as 30 inches and penetrate deep into the ship's remains.

The technological innovations Cameron pioneered for these dives had applications far beyond filmmaking. His development of high-intensity lighting systems, 3D camera rigs capable of operating under extreme pressure, and advanced sonar mapping techniques contributed significantly to deep-sea exploration technology. The footage captured during these expeditions provided researchers with invaluable data about the ship's deterioration and structural condition.

Authentic Details That Made It to the Screen

Cameron's firsthand observations during his dives dramatically influenced the film's production design. Every detail, from the pattern on the carpets to the arrangement of deck chairs, was meticulously researched and recreated based on what he witnessed at the wreck site and historical records. The director noted the haunting presence of personal items—shoes, luggage, and everyday objects—that gave silent testimony to the lives lost in the disaster.

The opening and closing sequences of "Titanic" feature actual footage from Cameron's expeditions, seamlessly blended with dramatic scenes. These authentic shots of the rusted bow, fallen debris fields, and eerie interiors provided a sobering reality check that grounded the film's romantic narrative in historical tragedy. The contrast between the ghostly wreck and the vibrant recreation of the ship in its glory days created an emotional resonance that mere special effects could never achieve.

Documentary Projects and Continued Exploration

Cameron's deep-sea adventures extended well beyond the Titanic's theatrical release. In 2003, he produced and directed "Ghosts of the Abyss," a 3D documentary that took audiences on a virtual dive to the wreck site. The film featured actor Bill Paxton, who starred in "Titanic," accompanying Cameron on dives to explore areas of the ship that had previously been inaccessible. Using advanced robotics and imaging technology, they captured stunning footage of the grand staircase, passenger cabins, and other interior spaces.

Cameron continued his documentation work with several television specials, including "Last Mysteries of the Titanic" and "Titanic: 20 Years Later with James Cameron," each utilizing increasingly sophisticated technology to reveal new details about the disaster. His repeated visits to the site have created a unique longitudinal study of how the wreck deteriorates over time, providing scientists with critical data about deep-sea preservation and decay.

The Legacy of Exploration

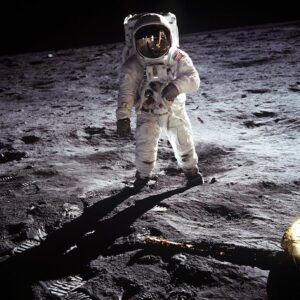

James Cameron's dedication to exploring the Titanic wreck transformed him from merely a filmmaker into a legitimate oceanographer and explorer. His work earned him recognition from scientific institutions, and he was made a National Geographic Explorer-in-Residence. The director's commitment to deep-sea exploration continued with his record-breaking solo dive to the Mariana Trench's Challenger Deep in 2012, the deepest point on Earth.

The intersection of Cameron's artistic vision and scientific curiosity created something unprecedented in cinema history. His insistence on diving to the actual wreck site—at tremendous expense and personal risk—demonstrated that for some filmmakers, authenticity isn't just a goal but an absolute necessity. The success of "Titanic" proved that audiences respond to genuine passion and meticulous attention to detail, even when those details come from two and a half miles beneath the ocean's surface.

Cameron's underwater expeditions to the Titanic represent more than a director's research for a film. They exemplify how artistic endeavors can advance scientific knowledge while creating entertainment that resonates across generations. His pioneering work continues to inspire both filmmakers and ocean explorers, demonstrating that the boundaries between art, technology, and science need not be rigid barriers but rather permeable membranes through which innovation flows.